The Uncanny Valley of Automation - Lessons from a Car Crash

A few days ago marked the one year anniversary of when I crashed my car. Like any accident - car or otherwise, there were many contributing factors, but the facts of the event are that I was distracted - I was looking for my phone to confirm an address, looked up and saw my car way too close to a car parked on the side of the road. A road that I would have sworn did not have as much of a curve to it before this trip. I contributed to the damage by hitting the accelerator instead of the break while turning the wheel sharply. Accelerator or no, I still would have hit the trailer behind the car on the road.

After this point, I’m less clear on what happened. After hitting the trailer behind that car, with the added acceleration, my car gripped part of the trailer or SUV that was pulling the trailer, and my car ended up on its side. I and my daughter in the back were buckled in our seats the whole time, her in her car seat and me in the driver’s seat. Before I knew what had happened, the car or my phone, I’m not sure which, had dialed 911. I did my best to explain what happened and where I was. Like many accidents, I was close to home (crazily less than 0.3 miles from my front door). Following the call, passersby stopped to help. I don’t know any of their names, but they opened the rear passenger’s side door to get my daughter out of her seat. I was able to climb out of the window of the front passenger side door and hop down to the ground from the overturned car. Neither of us had any injuries and the paramedics that came to the scene and medical visits the next day confirmed this.

The pictures below show the extent of the damage and the hectic aftermath in the eerie light of police sirens while my car was on its side and after a tow truck flipped it back on its wheels.

What Went Right:

We both had our seatbelts on and a secure car seat.

Safety protocols in the car assisted in calling emergency help.

When the tow truck flipped the car back on its tires, the airbags had deployed. Either from the jolt of being back upright, or during the accident.

The car was structurally sound throughout the accident - we were able to open all doors and windows and access electrical systems up until days later.

Insurance covered most of the damage, and I was in a replacement car a few weeks later (probably with higher insurance rates… ).

The available data from the car’s cameras and sensors makes understanding what happened much clearer.

My speed was below 30 mph for the entire trip - had it been higher, it could have been a lot worse.

What Contributed to the Accident:

I was exhausted. Not from anything in particular on this day, but cumulatively. We had finished moving to a new neighborhood a few weeks ago with an almost-two-year-old, and living the life of a parent trying to adjust a child to sleeping in a new place and still working a full day after closing on a house, packing and moving in the weeks leading up to the accident was a recipe for exhaustion.

I did not know local roads well (hence looking for an address).

I had been using Tesla’s Full Self Driving (Supervised) feature more and more for the past year. FSD (Supervised) was not enabled during the drive and didn’t contribute to the car’s reaction. The reliance on a driver assistance system did however lead to complacency on my part, and in turn a loss of situational awareness due to an over-reliance on automation.

So What’s the Point?

This is not written as a hit piece against Tesla. (Although some will read it that way. But at least note there was no fire, exploding battery and the generally high safety ratings of Teslas from multiple sources.)

I’m writing this as a caution to understand the limits of automation - read as AI, ADAS or any other upcoming system. Automation and AI are at the uncanny valley - a term often used to describe how computer graphics render human faces where they do not appear completely natural and we can’t explain completely why that is. Similarly, with automation of daily tasks, technology appears helpful, until certain realities happen and a situation goes sideways.

While Tesla does have its approach to automation systems using cameras as its main sensor source, many cars are also adding automated driver assistance systems (ADAS). We are coming to a point where many of these systems are becoming increasingly capable, to the point of fully driving the vehicle. My point for sharing what happened is to reiterate what’s said over and over again - that it’s when we’re in this transition period - when automation is very capable - whether it’s your latest ChatGPT answer, or your car helping you on the highway - when the most attention is needed. Until the capabilities of these tools are well beyond what humans can do, caution is needed.

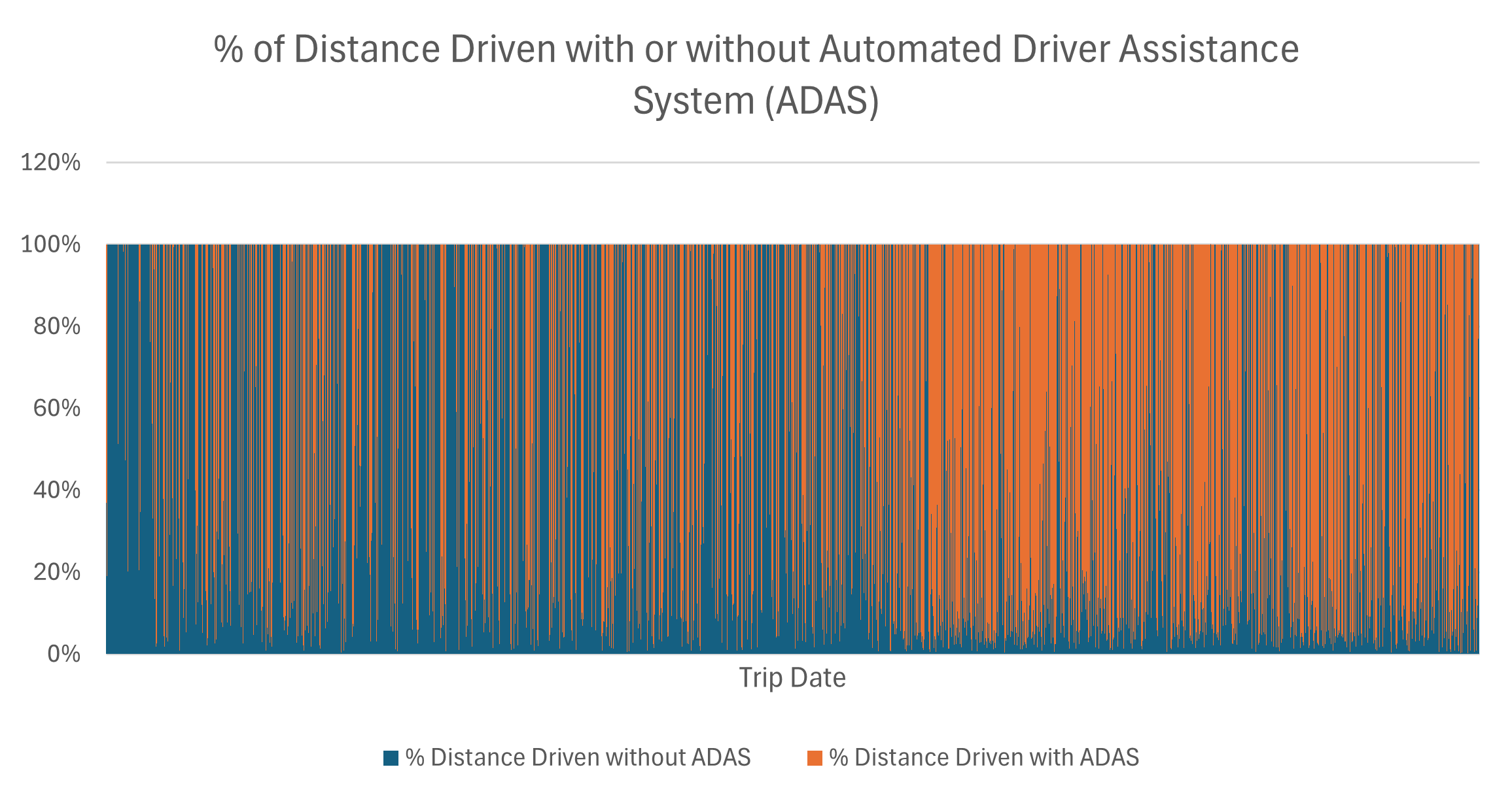

The graph below shows the increasing amount of mileage I used the ADAS system compared in orange compared to driving on my own in blue. The time scale is for about 15 months, from July 2023 to October 2024. In this time, the software received frequent updates and I become more comfortable relying on it to get me from Point A to Point B.

I was fully away of its capabilities and faults but still was caught of guard in the moment of a strange situation. It’s similar to many high profile aviation accidents where a sequence of events leads to over-correcting or being complacent with automation. A summary of two occurrences where automation led to an unfortunate accident are below:

Air France Flight 447 - The autopilot disengaged after the pitot tubes iced over, leading to inconsistent airspeed readings. The non-flying pilot, likely suffering from automation surprise and a failure of basic manual flying skills (due to over-reliance on automation), incorrectly applied and maintained a nose-up control input, which contradicted the aircraft's stall protection logic and caused the A330 to enter an unrecoverable aerodynamic stall. The pilots did not recognize the stall condition until it was too late.

Turkish Airlines Flight 1951 - A faulty radar altimeter on the captain's side caused the autothrottle to retard thrust to the idle setting prematurely during the approach to Amsterdam. Crucially, the crew was not monitoring the airspeed, assuming the autothrottle was maintaining the correct speed. When the speed dropped dangerously low, the pilots were late to react and failed to increase thrust manually, leading to a stall and crash just short of the runway. This is a classic case of complacency and the loss of situational awareness due to over-reliance on automation.

For those who are curious, I share the data for what happened on the day of the accident below. I was at fault, clearly. I am lucky? blessed? that things did not turn out another way, especially for my daughter.

So the least I can do is share my story in the hopes that others can be vigilant when needed. Moreover, I’m writing this as an anniversary reminder to myself that life is short—we’re not guaranteed to walk away from any event.

Build up your fitness so you can help yourself and others when misfortune occurs, read your history so you can prevent repeating the same mistakes over again, and get some sleep. We could all use some more rest.